Working with Fixed-Point Numbers in Rust Using the fixed Crate

In this post, we take a quick look at fixed-point numbers and how to use them in Rust. We also briefly explain why they are useful in embedded and other scenarios, with examples using the fixed crate. While revising the Pico Pico book (an embedded Rust book for the Raspberry Pi Pico 2), I was working on the PWM chapter for controlling servo motors. In that chapter, embassy-rp uses a fixed-point number to store the PWM clock divider. Both the integer and fractional parts are stored together in a single field called divider, using a type from the “fixed” crate. Instead of explaining fixed-point numbers briefly there, I decided it made more sense to write a separate blog post. That is how this post came to be. Here, I will give a short introduction to fixed-point numbers and explain how to use them in Rust. A fixed-point number is a way to represent fractional (non-integer) values using only integer arithmetic. Unlike floating-point numbers (like This idea is explained well in the fixed crate documentation, but let me give a quick overview. The key idea is this. If you have n total bits and you choose f bits for the fractional part, then you automatically have Fixed-point numbers maintain uniform spacing between consecutive values throughout their range. The step size formula is For example, consider a 16-bit fixed-point number where 4 bits are used for the fraction. Here, f = 4, so the remaining 16 - 4 = 12 bits are used for the integer part. With 4 fractional bits, the smallest step size is 1 / 2⁴ = 0.0625. This means fractional values are represented as multiples of 0.0625. After 0.0625, the next value is 0.125, and the numbers continue to increase in fixed, evenly spaced steps. Let’s use a 16-bit unsigned number as an example. Normally, to store an integer like 5, the binary representation would be For instance, if we allocate the last 4 bits for the fraction, we have 12 bits left for the integer. Here’s how the bits map to their values: The decimal point (shown as If we need more precision, we can allocate more bits to the fractional part. With 8 fractional bits, we get: With 8 fractional bits, our smallest representable value is 2⁻⁸ = 0.00390625 (1/256), giving us finer precision but reducing the maximum integer we can represent. The fixed crate provides fixed-point number types in different sizes. The number in the type name tells you how many bits are used in total. For example, FixedI8 and FixedU8 are 8-bit fixed-point numbers. FixedI16 and FixedU16 are 16-bit types. In the same way, there are 32-bit, 64-bit, and even 128-bit fixed-point types, both signed (FixedI*) and unsigned (FixedU*). What makes these types flexible is the extra generic parameter that controls how many bits are used for the fractional part. For example, The crate also provides convenient type aliases so you do not always have to write the generic form. For example, U12F4 represents a unsigned fixed-point number with 12 integer bits and 4 fractional bits. You can use it directly like this: Create a new Rust project, add the To make things easier to understand, the example prints the same value in several different forms. First, it prints the fixed-point value itself. The :.4 formatting is only for display and shows four digits after the decimal point. Next, it uses helper methods from the fixed crate to print the fractional part and the integer part separately. Then it prints the binary representation in two different ways. The first binary print ({:b}) is a human-friendly representation provided by the fixed crate. It inserts a binary point to show where the fractional bits are. This can feel a little confusing at first glance, at least it did for me. But once you get used to reading it, it actually becomes easier to reason about fixed-point values. The second binary print uses to_bits(), which returns the raw 16-bit value stored internally. For clarity, the integer bits and the fractional bits are manually separated with an underscore when printing. If you run this code, you will see output like this: When I first saw Binary with Fraction repr: 101.11, it was confusing. My brain read the 11 in the fractional part as the number three. That is not how fixed-point fractions work. To understand what this value really represents, let’s look at the binary representation. The integer part is straightforward. The bits 101 represent the value 5 using normal binary rules. The fractional part is where the confusion usually comes from. Each fractional bit represents a negative power of two. That adds up to 0.75. Let’s look at one more example. This time, I try to represent the value 20.3. I keep the same fixed-point configuration as before, with 4 fractional bits. If you expect the line assert_eq!(f_u16, 20.3125) to fail, you might be surprised. It does not fail. The code compiles successfully and produces the following output: This happens because 20.3 cannot be represented exactly using this fixed-point format. As stated earlier, the fractional part can only increase in steps of 1 / 2^f. With 4 fractional bits, the step size is: So the fraction 0.3 must be rounded to the nearest multiple of 0.0625. The value 0.3125 is a valid multiple: In the binary, it is represented like this: If we calculate the fractional part: On the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 (RP2350), the PWM clock divider controls how fast the PWM counter runs. The PWM counting rate is calculated by dividing the system clock frequency by this divider value. The divider register stores the value using a fixed point format. It is split into an integer part and a fractional part. The upper 8 bits represent the integer portion of the divider, and 4 bits represent the fractional portion. Together, these bits form a fixed point number, allowing finer control over the PWM frequency. The following code snippet is from the rp-pac crate and shows how the divider register is defined. Although the register is defined as a 32 bit unsigned integer, only 12 bits are actually used. Of these, 8 bits are used for the integer part and 4 bits for the fractional part. In the embassy-rp crate, the divider is represented using a type from the fixed crate. When configuring the PWM hardware, this fixed point value is converted into a u32 and written directly to the register.

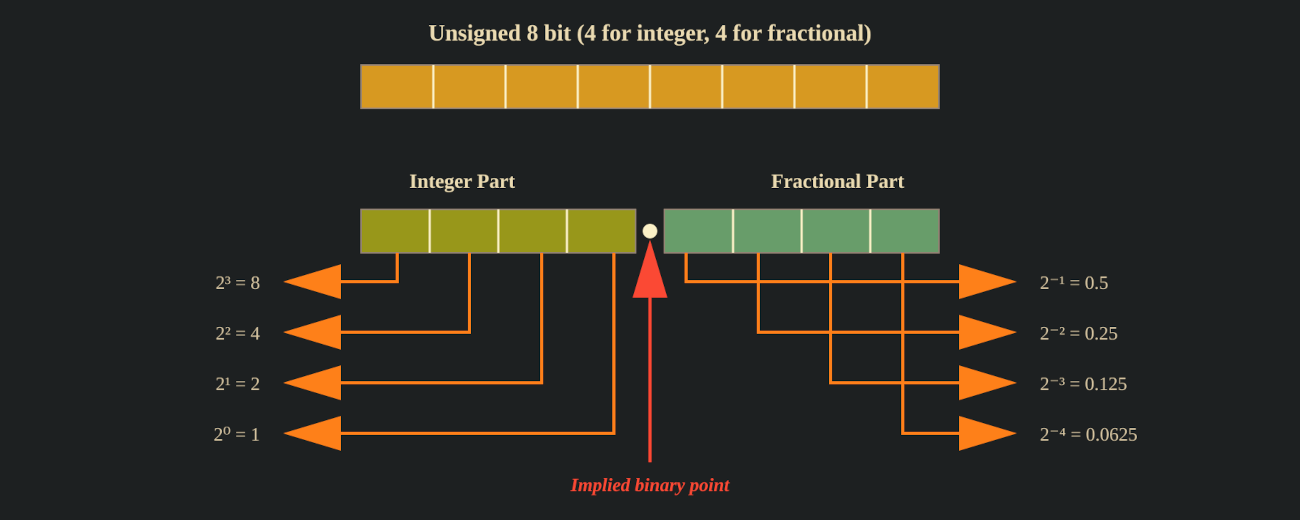

What is Fixed Point?

f32 or f64), fixed-point numbers reserve a predetermined number of bits for the fractional part. This makes them predictable, fast, and ideal for embedded systems where floating-point hardware might be unavailable or too slow. Understanding Fixed-Point Notation

n - f bits left for the integer part. Once this split is chosen, the position of the decimal point is fixed.1/2^f. Binary Representation

0000_0000_0000_0101. With fixed-point representation, we dedicate a predetermined number of bits for the fractional part, depending on our precision needs. The remaining upper bits store the integer part. Example: 4 Fractional bits

Bit Position 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 . 3 2 1 0 Weight 2¹¹ 2¹⁰ 2⁹ 2⁸ 2⁷ 2⁶ 2⁵ 2⁴ 2³ 2² 2¹ 2⁰ 2⁻¹ 2⁻² 2⁻³ 2⁻⁴ . in the table) is just for our understanding, it doesn’t actually exist in memory. With 4 fractional bits, the smallest value we can represent is 2⁻⁴ = 0.0625, giving us a precision of 1/16. Example: 8 Fractional bits

Bit Position 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 . 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Weight 2⁷ 2⁶ 2⁵ 2⁴ 2³ 2² 2¹ 2⁰ 2⁻¹ 2⁻² 2⁻³ 2⁻⁴ 2⁻⁵ 2⁻⁶ 2⁻⁷ 2⁻⁸ Fixed Crate Types

FixedU16<extra::U4> is a 16-bit unsigned fixed-point number where 4 bits are used for the fraction. That leaves 16 - 4 = 12 bits for the integer part. If you use FixedU16<U0>, there are no fractional bits, so it behaves just like a normal u16.use U12F4;

Example 1

fixed crate as a dependency, and replace main.rs with the following code.use ;

use types;

Bit Position 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 . 3 2 1 0 Stored Bit 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 Weight 2¹¹ 2¹⁰ 2⁹ 2⁸ 2⁷ 2⁶ 2⁵ 2⁴ 2³ 2² 2¹ 2⁰ 2⁻¹ 2⁻² 2⁻³ 2⁻⁴

Example 2

use ;

use types;

1 / 2^4 = 0.06250.0625 × 5 = 0.3125Bit Position 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 . 3 2 1 0 Stored Bit 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 Weight 2¹¹ 2¹⁰ 2⁹ 2⁸ 2⁷ 2⁶ 2⁵ 2⁴ 2³ 2² 2¹ 2⁰ 2⁻¹ 2⁻² 2⁻³ 2⁻⁴

In Raspberry Pi Pico 2 (RP2350)

;

if config.divider > from_bits

p.div.write_value;